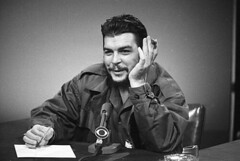

Che Guevara, Argentine-Cuban Revolutionary Speaks to CBS-TV's "Meet the Press" on December 13, 1964 (AP Photo).

Originally uploaded by Pan-African News Wire Photo File

by Key Martin

In January 1965, Ernesto "Che" Guevara gave up his post as

Minister of Industry in the new revolutionary Cuban government and returned to the guerrilla struggle. On Oct. 9, 1967, just 25 years ago, he was captured by CIA operatives in Bolivia and murdered.

Those were tumultuous years in the movement. Some of the events that provided the context for Che's decision were:

- A sharp turn to the right in U.S. Latin American policy in favor of coups, military regimes, greater repression and death squads. This came as U.S. economic domination tightened and living standards fell.

- White mercenary columns marched through the Congo, destroying the liberation movement of the late Patrice Lumumba and leaving a gruesome trail of massacres.

- President Lyndon Johnson began massive bombing raids on North Vietnam and sent hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops into the south.

- The Civil Rights movement in the U.S. was raising demands with a power and anger that could no longer be ignored by the government.

Before Che disappeared, he made a last appearance at the United Nations and also met with a group of supporters in New York. At the time, none of us knew the real purpose of the meeting was to say goodbye. The discussion extended until midnight and covered a broad range of topics, from guerrilla movements in Latin America to the impact of the U.S. blockade on Cuba.

MEETING WITH CHE

Vince Copeland led the Workers World Party delegation to the

meeting. He edited Workers World newspaper for its first ten

years. A former steel worker and union leader (21,000 workers had gone out on strike when he was fired from the sprawling Lackawanna Steel Works outside Buffalo during the McCarthy period), he later wrote of the meeting:

"We were seated around Che in a semi-circle. [He was] sitting on the floor, probably to put us at our ease.

"Che was as handsome as his pictures and informally witty as he was reputed to be. `A revolutionist has to be a little loco,' he told us with a sympathetic smile, when someone asked him what were the human qualifications necessary to create a movement to destroy capitalist oppression.

"You would never have known by anything in his manner that he was the author of the book `Guerrilla Warfare'--and more significantly a great practitioner of its lessons. Several of us remarked afterwards on the total absence of build-up and pomp and `greatness' that every big shot in the capitalist world surrounds himself with on such occasions.

"He didn't at all have the `commanding presence' that great

leaders are supposed to have. Nor did he speak with an air of

special wisdom or was he overconscious of his position. He seemed like a person who would find it absolutely impossible to pontificate about anything at all, including that which he had the most right to speak authoritatively about--guerrilla warfare.

"He was just as serious about the number of eggs produced in Cuba as he was about the possibilities for world revolution. At that time, there was a great deal of talk about rationing of food in Havana. And with many of the statistics at his finger-tips, he made the fundamental point that for the great masses of Cuba, rationing was a tremendous step forward, because formerly they had had practically nothing and now they were being fed, while the formerly well-to-do had to wait.

"No one felt any more strongly than Che Guevara himself that he could not fail, and that the socialist revolution was inevitable.

By the same token, Che also was one of the foremost among those brave spirits throughout the ages who have taken to arms against oppression, who have sounded the clarion call to struggle for a better world. He felt deeply that one `who wills the objective must will the means thereto.' And his advocacy of armed struggle, like his example of laying his own life on the line, shall not perish with him."

In addition to Vince, a delegation of youth from Workers World was present, including Deirdre Griswold (the current editor of Workers World), Ellen Catalinotto (an anti-war community organizer), and this writer. Black Civil Rights activist Mae Mallory was also present.

Some years later we read Che's diary, a moving account of his

experience in the guerrilla struggles in Bolivia, of the problems and sacrifices they faced, and his political thinking in the final months of his life.

When he saw his CIA murderer come into the room in Bolivia, Che, lying captive and wounded on a cot, said merely, "Now you will see how a real revolutionary dies."

A few weeks after his murder, Workers World youth, active in Youth Against War and Fascism at the time, distributed hundreds of portrait-placards with the caption `Avenge Che.' This was at the massive march to protest the Vietnam war that surrounded the Pentagon, the first demonstration that began to show the revolutionary militancy in the youth movement that the 1960s became famous for.

Che's picture haunted the Pentagon that day and will continue to haunt them for generations to come.

1 comment:

What a man! All respect for the great man! Greetings from London, UK

Post a Comment